Writing as Revenge

January 23, 2026 § Leave a comment

I’ve been out of work for over a month now, and while I feel antsy, it’s taken a while to permit myself to use the time to write. When a writer is employed with a day job, they invariably envision how much writing they could get done if they weren’t working. Part of the reason I haven’t been writing, I think, is a sense of guilt that I should be doing other things pertaining to the job search.

One of the things that motivates me to write is a sense of revenge. Having been laid off, it might not surprise anyone that I am harboring a sense of bitterness. It occurs to me that this is a time when that motivator should be looming large, and I should use this time to find my words.

I have always appreciated this video about failure and revenge from the writer Elizabeth McCracken (“A Long Game”), whom I have had the privilege to interview in the past. “A well-nourished, very private sense of revenge has enough heat and light to power a city, never mind a novel,” she says.

McCracken speaks about revenge as a motivator as a response to failure, but I am drawn to the idea of writing as an act of revenge itself. You can base characters loosely on people who have affronted you and give them their due. You can use that zingy comeback—the esprit d’escalier—that didn’t come to you on the spot. You can play out scenarios that in real life got cut short, or follow decisions that never got made. Broadly, writing offers the chance to confront the bizarre and reconcile the unexpected with patience and wisdom.

And naturally, I have a lot of things to say in response to a scenario that got cut short. Writing, among other things, can blaze a path that will bring you to that sense of closure.

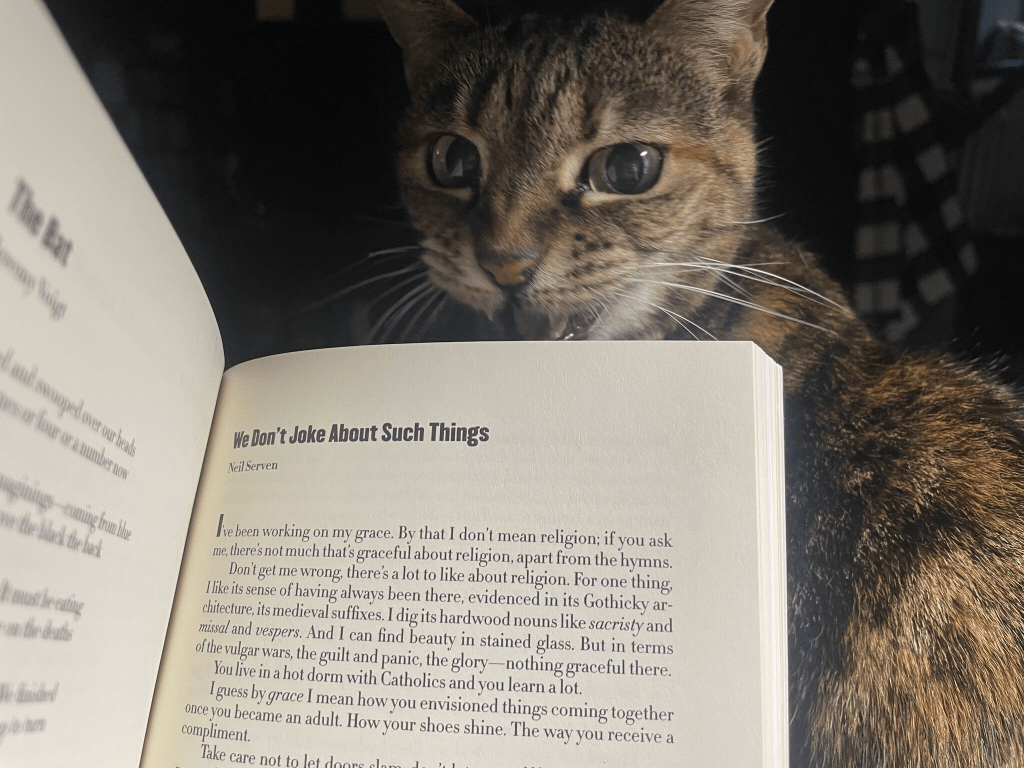

We Don’t Joke About Such Things in Post Road

May 31, 2025 § Leave a comment

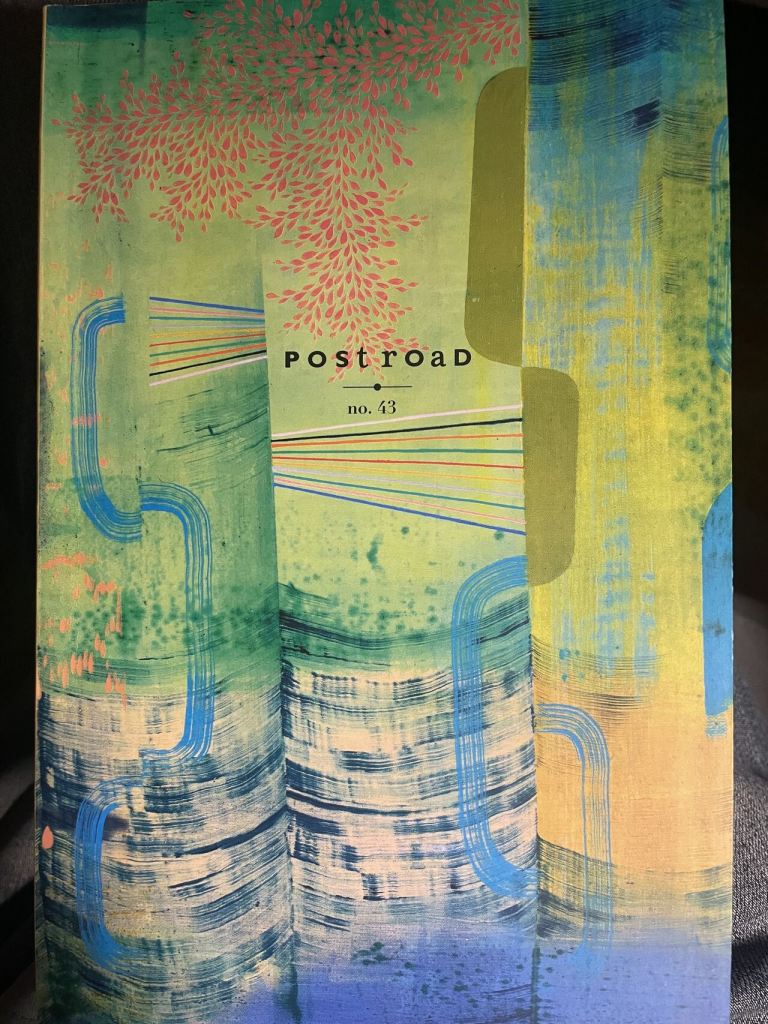

In the mail: Post Road no. 43, featuring my story “We Don’t Joke About Such Things.” This story has been through a long journey before arriving at this destination. It’s gone through several revisions–the title is one I even used for an older story that looks nothing like this one–and earned honorable mentions in a couple of contests. It’s a story I workshopped a number of years ago at the Bread Loaf Writer’s Conference in a class led by Alix Ohlin, a brilliant and thoughtful group among whom several members have since published novels. Their suggestions were vital in shaping the story to its final form.

The David Style

March 2, 2025 § Leave a comment

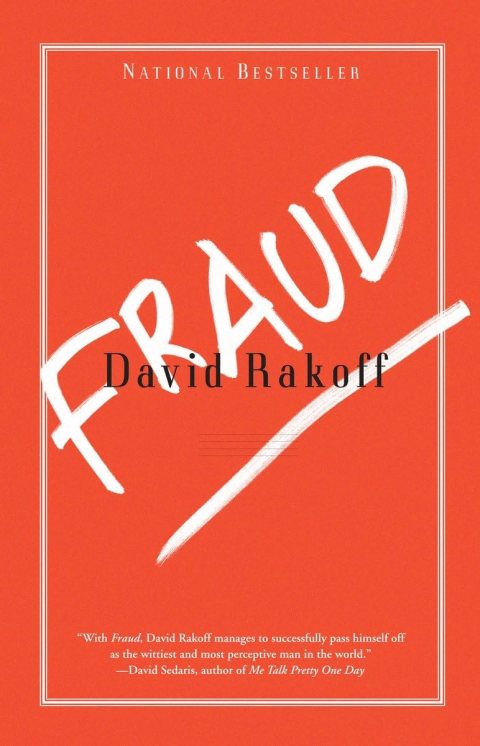

I decided to read David Rakoff’s Fraud, which had been sitting on my shelf for a while. I had bought it used and remembered there being a lot of hype surrounding the book when it came out, I think because Rakoff was viewed as an heir apparent of sorts to David Sedaris. Like Sedaris, he had a number of essays featured on This American Life. Some of the essays in Fraud were featured on the show, and have the indicators of TAL material—immersive experiences, some interviews, all interjected with light, wry humor.

As I read it, though, I was thinking of the essays of David Foster Wallace—the kind of assignment journalism he attempts in A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again. (I’m thinking of Wallace’s pieces on the Illinois State Fair and the cruise ship excursion, to be specific.) These essays are fun and entertaining reads, but they carry a bit of a haughty, somewhat hostile Gen X attitude, through the lens of someone who can’t believe the people around him are taking themselves seriously and having a good time. It carries the insinuation that we, the reader, would never stoop to participating in such activities ourselves.

The essays in Fraud tackle similar “you had to be there”-style assignments: Rakoff’s time at a New Age retreat center, his attendance at a wilderness & survival school in New Jersey, an orientation session for teachers from Austria for positions in the New York City public school system. Rakoff’s writing is less intentional in its aim, less hostile, a little more sincere and curious, but it often still leaves its subject hanging out to dry while we are supposed to share the author’s perplexity. I have not listened to This American Life in a long while, so maybe I’m wrong in assuming this, but this approach to essay writing strikes me as belonging to an era that has passed—writing with less of a sense of elevation and more about using subjects as marks to showcase wit. Given the shared first names of these three notable examples, I’m inclined to think of this as the David Style.

Rakoff died in 2012 from complications at the very young age of forty-seven. The final essay in Fraud obliquely refers to his diagnosis of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. (I thought of Janet Hobhouse having her ovarian tumor discovered at the end of The Furies.)It’s one of Rakoff’s few personal pieces in the book, though it strives to be about something other than himself.

What I Read in 2024

January 1, 2025 § Leave a comment

- The Tailor of Panama, John Le Carré

- Sweet, Soft, Plenty Rhythm, Laura Warrell

- The Last Thing He Wanted, Joan Didion*

- Bonjour Tristesse, Françoise Sagan

- Wayward, Dana Spiotta

- The Waste Land and Other Writings, T.S. Eliot

- Lit, Mary Karr

- Manhood for Amateurs, Michael Chabon

- The Cartographers, Peng Shepherd

- Hunger Makes Me a Modern Girl, Carrie Brownstein

- Liquid, Fragile, Perishable, Carolyn Kuebler**

- Varieties of Exile, Mavis Gallant*

- The Great American Novel, Philip Roth

- It’s Lonely at the Centre of the Earth, Zoë Thorogood

- The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald*

- Minor Characters, Joyce Johnson

- In Universes, Emet North**

- Olga Dies Dreaming, Xochitl Gonzalez

- Finding a Likeness, Nicholson Baker

- The Insides, Jeremy S. Bushnell

- The Guest, Emma Cline

- The Hydrogen Jukebox, Peter Schjeldahl

- The Night Guest, Hildur Knútsdóttir**

- Mostly Dead Things, Kristen Arnett

- Crook Manifesto, Colson Whitehead

- Blood at the Root, Patrick Phillips

- Creation Lake, Rachel Kushner**

- Speak, Memory, Vladimir Nabokov

- See Friendship, Jeremy Gordon**

- Always Happy Hour, Mary Miller

- There Is Happiness, Brad Watson

- The Seas, Samantha Hunt

- The Complete Novels, Jean Rhys*

- The Best American Short Stories 2024, Lauren Groff, ed.

- The Name of This Band Is R.E.M., Peter Ames Carlin

- The Ice Storm, Rick Moody*

*reread

**read as galley

Thirty-six is a steep drop from the 50 books I read last year, and I can’t account for what happened there. I didn’t vacation this year, and I took on greater responsibilities at work, which may have left me with less headspace. There was also, of course, the lingering specter of returning fascism. It was all over everything, prompting so much doomscrolling over engagement. They say that book sales see a decline in presidential election years.

Among these, a few of my favorites were galleys. Creation Lake was genuine Kushner, a cool narrator roaming around in a loose plot with space to do damage. The Night Guest was fast-moving horror that gave a window into Icelandic culture, while the similarly-named The Guest was smart and knowing around its coy young narrator. Emma Cline and Rachel Kushner remain two of my favorite writers working today. One thing that slowed me down was re-reading the novels of Jean Rhys—five in all, though I count them as one here—as I wanted to make my way around the cafes of gloomy foreign cities. Was glad to find Bonjour Tristesse out in the wild, finally.

I turn fifty this year. I am trying to make the novel make sense against a world of shifting threat, where people seem starved to make noise rather than add something. A short story got pushed back but is still due to come out in Post Road. I was fortunate to have a flash-fiction story treated with great editorial care by The Cincinnati Review. And one of the most personal pieces I’ve ever written, about the resentment I felt from growing up with chronically ill parents, appears in the current issue of The Pinch. All things equal, I can’t complain about where I am.

Ill Nature in The Pinch

November 17, 2024 § Leave a comment

The Fall 2024 issue (44.2) of The Pinch, the journal of the University of Memphis, is out today and I am thrilled to have an essay in it that’s one of the most personal things I have ever written. “Ill Nature” is about growing up with chronically sick parents and the resentments that I carried over into adulthood.

I’m grateful to Managing Editor Mia Day and the staff at The Pinch for giving this piece that means a lot to me such a good home.

How Dogs and Aliens Think

October 28, 2024 § Leave a comment

Brad Watson died in 2020 at the age of 64, the same age as one of my favorite short story writers, Frederick Busch. I hadn’t really known Watson’s work at the time, but other writers celebrated both his stories and the human who wrote them. He wrote two novels, Miss Jane and The Heaven of Mercury (the latter a finalist for the National Book Award), and two collections, Last Days of the Dog-Men and Aliens in the Prime of Their Lives. I was never able to find them in any bookstore I visited.

There’s now a posthumous collection available, There Is Happiness, published by W. W. Norton & Co., with a foreword by Joy Williams. It contains both of the title stories from Last Days and Aliens. Many of the stories have a Southern flavor (Watson was born in Mississippi) but are not as yarny as Barry Hannah’s or sentimental as Truman Capote’s; they are often humorous but not reductively so, weighted with sincerity even as they veer into the strange. Characters wear their flaws and get bruised from fights and embarrassment but persist in their efforts to strive upward. Just as with any Joy Williams collection, there are a good number of dogs, some with quirkier personalities than their humans, such as the dog in “Terrible Argument,” who is an unwilling witness to the combative relationship between a nameless couple. The dog gradually becomes the story’s motor:

The man and woman came by one day and took her home, and were kind to her, but almost immediately the daily loud barking and snarling started up, and even if she could usually tell when it was about to start she was always frightened and wanted to run away. Now here she was beneath the coffee table, licking her paws, with their leash fastened to the collar about her neck, and nowhere to go. No walk. No drive up into the mountains to chase squirrels. No quick trip to the prairie to jump jackrabbits, harass the cowardly pronghorn herd. She could rip open the back screen, jump the fence, and walk until another man or woman or couple saw the leash and took it up. She could offer herself to someone else this way, take her chances.

Williams was good friends with Watson, and after his death she wrote about driving up to his Wyoming ranch to mourn with his wife, Nell. Around this same time, I got to see a video recording of Watson giving an incredible lecture at Bread Loaf that discusses a story by Williams, “The Farm,” as an example of a writer using craft as a way to unlock potentialities and recognize a story’s natural force.

Maybe the reason I had trouble finding his books is that I live too far north. But I was glad that There Is Happiness gave me a chance to experience the work of this thoughtful writer.

Red Eye at Cincinnati Review

September 6, 2024 § Leave a comment

I have a new flash-fiction story called “Red Eye” up at The Cincinnati Review today as part of their miCRo series. You can read it here as well as listen to a recording of me reading it.

With thanks to editor Lisa Ampleman, who introduces with this kind note:

This story makes me think about the different people we become over time—and how we create artifacts of past selves in photographs and papers (something I have familiarity with lately). Neil Serven’s story gives full complexity of character to the woman who is the speaker’s mother through the speaker’s contemplation of such artifacts.

Looking Back and Ahead

December 31, 2023 § Leave a comment

A sloppy list of the books that I enjoyed reading in 2023:

- The Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard

- Either/Or, Elif Batuman

- Fun Home, Alison Bechdel

- Relentless Melt, Jeremy P. Bushnell

- My Education, Susan Choi

- I Meant It Once, Kate Doyle

- Dirtbag, Massachusetts, Isaac Fitzgerald

- Nothing Special, Nicole Flattery

- Tinkers, Paul Harding

- The Price of Salt, or Carol, Patricia Highsmith

- Cherry, Mary Karr

- The Dinner, Herman Koch

- In the Dream House, Carmen Maria Machado

- A Burning, Megha Majumdar

- Brother and Sister Enter the Forest, Richard Mirabella

- Lunch Poems, Frank O’Hara

- The Words, Jean-Paul Sartre

- Jimmy Corrigan, The Smartest Kid on Earth, Chris Ware

- Weather, Jenny Offill

- The Beak of the Finch, Jonathan Weiner

- Loitering With Intent, Muriel Spark

- Crying in H Mart, Michelle Zauner

Varnish Day at Monkeybicycle

December 8, 2023 § Leave a comment

But to Evelyn, death was its own uncanny presence. It showed up like a clown in a horror film, it rendered you ridiculous, it could make any word a last word, even if that last word was sponge. All you could do was laugh at it.

Sometime earlier this year my friend Soren posted that it was Varnish Day at the casket factory near where she lives, and that it sounded like the beginning of a Tom Waits song. I commented that I wanted to use the line as the first line of a story.

That’s what I did, and now it’s been published at Monkeybicycle. With immense thanks to Soren for the inspiration and to editor James Tate Hill for giving it a lovely home.

Paperback Flex

November 5, 2023 § Leave a comment

At Esquire, Isaac Fitzgerald (Dirtbag Massachusetts) writes a love letter to the paperback, noting that their durability and affordability make for a flexible, versatile reading experience:

But a paperback is built for adventure. Paperbacks are light, and—as already mentioned numerous times in this essay—foldable. If you forget one at the bar or by the swimming hole, you will not mourn, for the book will be found by somebody else, and if you haven’t finished it before you lose it, don’t worry—you can buy a new one for the price of a drink or two, not an entire meal.

A thing we have noticed since we acquired the bookstore is that carrying both used and new books means we see a wider range of customers. Our town is by no means wealthy, so one thing we like is the ability to have cheaper used options available for customers who only have a few dollars to spring on a book. When I am out and about I try to keep a small paperback with me for idle times like when I am waiting for a takeout order—a small one fits in my hoodie pocket, and I feel like my time is more richly spent getting in a couple pages of a novel then scrolling mindlessly on my phone.

But publishing seems to be getting away from mass-market fiction, even the genres. There was a time when the shelves in the mystery and science fiction sections of chain stores were cut to accommodate the old-fashioned John Grisham, Patricia Cornwell-sized mass-market paperback. Now publishers are tending toward trade-paper-sized titles even for genre writers like Ruth Ware or Louise Penny, and the cheap newsprint mass-market seems to be going extinct.

That doesn’t necessarily change my ability to read in public, apart from the need for bigger pockets. But it does affect the customer for whom we try to provide affordable books. Pricing has consequently soared as well—both due to the higher-quality paper and the seeming inflation that Amazon has caused. Publishers can inflate prices knowing that the largest retailer for books is going to discount them heavily as a loss leader. They’ve essentially taken a side against independent booksellers by default.