On Bowling Alleys at The Smart Set

January 5, 2018 § Leave a comment

I have written about my love of bowling before, but my essay “Halfway Back to Worcester,” published today at The Smart Set, is my most comprehensive piece on the subject yet. It is about the vanishing of the independently owned bowling alley from the American landscape and the problems that the bowling industry faces not just from competing activities but from disrupting influences in the marketplace that treat the game as something other than a serious sport.

I’m thrilled to share this piece and thankful to editor Melinda Lewis for giving it a home alongside some snazzy illustrations by Emily Anderson.

What I Read (And Wrote), End of 2017

December 31, 2017 § Leave a comment

Cat’s Eye, Margaret Atwood

Everyone’s reading Margaret Atwood these days, but this book was recommended to me by H. after we got to talking about how bullies—from Nelson Muntz to Scut Farkus to Biff Tannen–are treated in popular culture. There’s a bully in Cat’s Eye, named Cordelia, whose personality is large and divisive and who casts a long shadow over the adolescence of the narrator and protagonist, Elaine Risley. But Cat’s Eye is more broadly a book about the natural undercutting that occurs in female friendships and how they carry over into adulthood and shape identity.

Elaine is an artist who grew up in Toronto and now makes her home in Vancouver. She is returning to Toronto for a gallery opening that is a retrospective of her career as a painter. The return prompts her to revisit her past, as she anticipates possibly running into Cordelia.

I really liked how Cat’s Eye was paced, and how its revelations were timed; this is not something I tend to pay enough attention to in novels. The retroactive narration is relayed with wry distance by the adult Elaine. It is not accidental that one of her frequent painting subjects is Mrs. Smeath, the evangelical mother of Elaine’s childhood friend Grace, who encourages Elaine to join the family at church and whose judgments are a heavy influence on Elaine’s image of herself. As a woman of middle age with a successful career and a lifetime of having her worked talked about by critics and explained wrongly back to her, she exhibits a caution as she selects and dredges memories from childhood and young adulthood and walks along the string:

Grace is waiting there and Carol, and especially Cordelia. Once I’m outside the house there is no getting away from them. They are on the school bus, where Cordelia stands close beside me and whispers in my ear: “Stand up straight! People are looking!” Carol is in my classroom, and it’s her job to report to Cordelia what I do and say all day. They’re there at recess, and in the cellar at lunchtime. They comment on the kind of lunch I have, how I hold my sandwich, how I chew. On the way home from school I have to walk in front of them, or behind. In front is worse because they talk about how I’m walking, how I look from behind. “Don’t hunch over,” says Cordelia. “Don’t move your arms like that.”

They don’t say any of the things they say to me in front of others, even other children: whatever is going on is going on in secret, among the four of us only. Secrecy is important, I know that: to violate it would be the greatest, the irreparable sin. If I tell I will be cast out forever.

But Cordelia doesn’t do these things or have this power over me because she’s my enemy. Far from it. I know about enemies. There are enemies in the schoolyard, they yell things at one another and if they’re boys they fight. In the war there are enemies. Our boys and the boys from Our Lady of Perpetual Help are enemies. You throw snowballs at enemies and rejoice if they get hit. With enemies you can feel hatred, and anger. But Cordelia is my friend. She likes me, she wants to help me, they all do. They are my friends, my girl friends, my best friends. I have never had any before and I’m terrified of losing them. I want to please.

Hatred would have been easier. With hatred, I would have known what to do. Hatred is clear, metallic, one-handed, unwavering; unlike love.

Known and Strange Things, Teju Cole

I hadn’t known that Cole was as prolific as he apparently is; I read Open City when it came out and since then he’s published another novel, Every Day Is for the Thief, and this collection of essays, many of which originally appeared in The New Yorker. He’s an accomplished photographer as well, and a frequent traveler of the world, and the subjects here effectively manage to cross-pollinate themes of beauty, history, identity, and the fleetingness of memory in art.

Cole’s literary interests intersect with mine: there’s a lot here on Sontag and Sebald, both writers who allowed the impression of the visual image to shape their work. I particularly like how he has reassessed the value of the image in the age of hyper-shareability. “More people than ever take photographs,” he writes, “and more photos than ever are being made.” The “curatorial uncertainty” has been unloosed in an age when robot cars take pictures of street corners and artists seize new ways to release the artistic potential in them. What even is a photograph when everything is being constantly photographed, no moment left unreplicated and unshared, even in places humans will otherwise never visit? What is it when the subjects or objects in the photograph no longer live or exist? Cole finds numerous angles with which to ponder these questions.

The Comforters, Muriel Spark

I bought this book used, and my copy came with some light but pointed underlining and annotations; I wondered, going through them, if the reader before me was having the same perplexed reaction to the book that I was. The Comforters was Spark’s first novel, published in 1957, five years before The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, and stood out for its distance from the realist trend of British fiction of the time. Its most significant twist is a metanarrative in which the young woman Caroline, a recently converted Roman Catholic, begins to hear the sounds of the typewriter and what is meant to be the voice of her own story being narrated back to her.

I read Miss Jean Brodie four years ago and my takeaway then was how its mock-theatricality seemed to contrast itself artfully in a story about loyalty and betrayal. There’s betrayal in The Comforters as well, and a subplot about a diamond smuggling ring run by an elderly woman who gives nothing away that she’s even capable of such underhandedness. This is the gag behind Spark’s fiction, it seems, that the potential for evil still lurks amid those who present themselves at their most polite and fussy. (Caroline’s initial reaction to the typing voice isn’t so much to be confused or frightened as offended at the notion that her path is already laid for her.) There feels an uncomfortable distance between intention and consequence that the manners hide, and complicated by the jibing at mental illness. “Is the world a lunatic asylum then?” Caroline asks. “Are we all courteous maniacs making allowances for everyone else’s derangement?”

Last Night, James Salter

I have enjoyed Salter’s work, particularly the novel Light Years, though I can understand a reader’s frustrations with him—adultery can only be trod so many times as a plot before the grass no longer grows back. The male gaze frames everything in these stories. That’s not exactly a groundbreaking observation about Salter, but here it seems shallower; Viri in Light Years and Philip in A Sport and a Pastime come more fully equipped with graces that at least distract from the intent.

Old lovers drop back into lives; people show up unwanted and desperate. A guest arrives late and drunk to a dinner party and tells the host, “you’re my friend , but … you’ll become my enemy.” He stumbles into the kitchen and “they could hear him among the bottles. He returned with a dangerous glassful and looked around boldly.”

The trajectory of each story locks predictably onto hurtful decisions. There’s the energy of managing relationships once thought safely shut:

He felt nervous. The aimless way it was going. He didn’t want to disappoint her. On the other hand, he was not sure what she wanted. Him? Now?

We forgive Salter for these basic arrangements, because he has a knack for writing a simple, graceful line that suggests a fullness of atmosphere. Characters stand idly while he manages to make you aware of darkness creeping in beyond a kitchen window. Pasts catch up.

Here Comes the Sun, Nicole Dennis-Benn

A year after I read Marlon James’s A Brief History of Seven Killings, here is another novel set in Jamaica, only a much different sector. Instead of the cocaine trade, this time it’s the hotel industry, where the façade of Jamaican paradise is presented for the wealthy tourist and business clientele.

Margot lives in a struggling town called River Bank and works at a Montego Bay resort, ostensibly as a front desk manager, but makes her real money as an escort for wealthy patrons, including the hotel’s owner. Leverage is measured by what can be weaponized, and Margot was taught at a young age that her weapon could be her body when her mother, who sells roadside souvenirs, offered her at the age of 14 for $600.

Now Margot’s objectives are two: leveraging herself a position managing a soon-to-be-built competing hotel, and the protection of her younger sister Thandi, who has the intelligence to pursue something beyond what Jamaica offers but risks falling into the same traps and temptations that lured and trapped Margot. Thandi secretly tries to lighten her skin, fearing that blackness is precisely what prevents any kind of opportunity in this tourists’ paradise of expectation and assignment. In conservative River Bank, Margot’s relationship with another woman, Verdene, has to be kept under wraps, but she is not afraid to use rumor and innuendo as a weapon herself.

There is a hard, unapologetic tone to this book. The arguments go on for pages: Margot’s resentment toward her mother; Thandi’s bitterness at being wagered on to break the family spell, when she would much rather pursue her talents as an artist; the ambivalence felt by Thandi toward her boyfriend Charles; and moreover, the constant on-their-feet calculations that must be performed in the name of survival.

Almost Crimson, Dasha Kelly

The relationship in Almost Crimson is between the title character, nicknamed CeCe, and her mother, who lives with mental illness. Successful in her work, with a supportive network of friends, CeCe has had to devote significant resources and mental energy to her mother’s care and as a consequence has had to make numerous sacrifices. Her mother, Carla, suffers from a crippling depression—lying immobile in her bedroom for days at a time–and with no father around, she has no real adult supervision until the understanding family of a childhood friend takes her in.

The choice that CeCe faces is made apparent when a loyal friend, dying of cancer, bequeaths CeCe her house, a significant distance from where her mother resides. In flashbacks, we get the story of how CeCe managed to pull herself up throughout her childhood, until the father who abandoned her suddenly pops back into the picture, essentially to whisper in CeCe’s ear about Carla and her affliction. There are emotions tugging from all directions: anger and resentment at her compromised youth; a daughter’s guilt at what seems like abandonment; and a rueful looking ahead at the possibility of ultimate independence and happiness.

There also might be one too many clearheaded and well-meaning friends, including a love interest, surrounding CeCe for her struggle to project any real stake. The hazard surrounding Carla is stated but never well exemplified; I would have expected at least one scene of a daughter’s overprotective panic that accompanies such caretaking relationships. For this reason, the scenes from CeCe’s childhood and grade school—with personalities that have to be manipulated–feel riskier and more alive.

One More Cup of Coffee, Tom Pappalardo

This book is from a local author who is known as a designer and creative-of-all-trades. You hear Tom Pappalardo’s voice in the radio ad for a local record shop and he draws cartoons in the alt-weekly. He’s had a hand in designing a number of signs for local businesses.

This is a lovely book that is an observational travelogue of the hangouts around Western Mass where coffee drinkers are likely to sit, chat, read, write, and be. But it provides a distinct level of comfort while achieving that. It allows us into the headspace that is familiar to anyone who has taken their notebook out in public, who has needed to get out and people-watch. Pappalardo writes with a subtle humanity and is relatable in terms of where he lets his mind wander–when he gets irrationally angry, or when he gets nostalgic for old neighborhoods.

The book is wholly designed by Pappalardo, text and graphics, and the illustrations in particular are bold-lined and of a distinctive style. You can find more of his designs here. He is remarkably able to render brand logos precisely and human shapes roughly and still have the two exist with unity on the page. The book is a sweet love letter to the 413.

My tally for 2017: 34 books read, including six re-reads. A handful were written by people I consider friends and people who are very much dear friends, including Kory Stamper’s Word by Word, discussed here. I thought Tom McAllister’s The Young Widower’s Handbook was gentle and patient, while managing to be funny, in telling how grief comes with no convenient process. I read Paul Lisicky’s The Narrow Door around the same time and appreciated its ability to portray the tug of two strong personalities settling into a friendship with moments of turbulence. I liked how Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts could fuse theory and narrative seamlessly while telling a story about a family. Roxane Gay’s Hunger deserved all the accolades it received as it unsparingly critiques our society’s values concerning body and image.

In my own writing, I also published essays for the first time: one about my father and the posthumous discovery of his having once reeled in a 452-pound tuna; and another about the era when highbrow writers and artists appeared in TV Guide magazine. I sort of started writing a novel, and have three pieces due to be published next year. I published stories in JMWW and Bodega, the latter of which was nominated for a Pushcart Prize. It was a year in which Americans were tasked with choices of what to value—common decency or vulgarity, blind aggression toward the vulnerable against an understanding of mercy. Against that backdrop, it felt like making and engaging with art came with a heightened responsibility. Art is its own rebellion. Its rejects the metrics that others set for us and tells the world that only we get to decide how we value ourselves.

These Things, They Go Away

October 10, 2017 § Leave a comment

Automatic for the People came out 25 years ago this week, and as fond reflections pour across the Internet (see Billboard, Newsweek, Salon, Mike Mills at Stereogum, and Bryan Wawzenek’s thoughtful and layered reading at Diffuser), I find myself in the complicated position of feeling nostalgia for a record that was already swimming in nostalgia.

(Wawzenek, as he has done brilliantly with Document and other albums, is following with even more thoughtful takes on each track from both a critical and historical angle).

Automatic for the People came out when I was 17 years old, between two hospitalizations during what was a very fucked-up year, more fucked up than teen years usually turn out to be. My grandmother died that January, the day of Bill Clinton’s inauguration. As much as I was going to miss my grandmother, I would really come to miss her house. I can still smell the living room carpet, see the colored-glass spice jars set out as decoration in the window above the sink, hear the wet sound of the screen door pulled open.

Automatic gets thought of as R.E.M.’s album of mourning, partly because of its black-gray album art, partly because of the immediate connotations brought up by “Try Not to Breathe” (“I will hold my head still with my hands at my knees”) and “Everybody Hurts,” partly because of the dirgy string arrangements on the early singles, “Drive” and “Man on the Moon.” I don’t think it’s coincidental that it’s the last album in the R.E.M. catalogue that makes any real allusion to the community in the band’s hometown of Athens, Georgia, that allusion being the title, which was a service slogan of a beloved restaurant in town (now closed) called Weaver D’s Fine Foods. We had gotten to know Athens, and its characters and structures, very well during much of the band’s residency with I.R.S. Records—between Wendell Gee offering advice to the young, Peewee dishing out pearls of wisdom in back of Oddfellows Local 151, or Mr. Mekis and his split personality living in a divided house (in “Life and How to Live It”). Automatic is, in so many ways, an album about growing up and leaving home.

At night I would put the disc in my Discman and walk out in a black hoodie and black jeans and lean against a tree at the end of my street, watching the traffic, in what probably came across as an unsubtle cry for help, though no police car ever came by to shine a light. I would lean against the tree and listen to men in their thirties sing about teenage independence (“Hey kids, where are you / Nobody tells you what to do”), then allusions to the music of my parents’ generation: an opener with the lyric “rock around the clock”; a poppy third track (“The Sidewinder Sleeps Tonite”) that cites Dr. Seuss while paying homage to The Tokens’ “The Lion Sleeps Tonite”; and a tenth track that mentions Elvis idolatry amidst the name-dropping of forgotten celebrities (Montgomery Clift, Andy Kaufman, Fred Blassie) and that feels like the kind of parental insistence of how things used to be that generates an eyeroll. Oh, the way Glenn Miller played.

The band knew that, perhaps for the first time, the majority of its audience was MTV-driven and younger than they were. So the songs are tinged with brotherly advice. They arrived at a time when I was trying to figure out if my irritableness and ennui was a sign of mental imbalance (“Maybe you’re crazy in the head”) now that I had made friends on Lithium regimens, when I waiting to see if my father would survive his heart transplant (“readying to bury your father and your mother”), when I was registered to vote and starting to pay attention to the news. I was learning to manage a checkbook. “Ollie, ollie, in come free” sounded to me like “income free.” Nothing’s free, so fuck me.

Even things like pay telephones, mentioned in “Sidewinder” (‘scratches all around the coin slot”) have since fallen by the wayside, and the idea of cutting keys to give out to (and subsequently demand back from) lovers somehow feels like generational hardware. Do kids go skinny-dipping anymore? Do they hitchhike (“pick up here and chase the ride” / “none of this is going my way”)? It’s so riskless and formal now that we have an app for that.

“These things, they go away / replaced by everyday.” Packing up my grandmother’s house. Pocketing my grandfather’s Swiss army knife for myself. Ironically, one seemingly dated theme from Automatic for the People that has come back into the fold: conspiracy theories. Michael Stipe practically foretells fake news (“nonsense has a welcome ring”), and naturally, if you believe they put a man on the moon you’ll believe that the earth is round, that the adults in your life who give you this cracked advice know what they are doing.

What I Read in January-July 2017

September 2, 2017 § Leave a comment

This is not a complete list by any stretch, but I’ve fallen well behind. There were re-reads in the mix, too—Frederick Busch’s Sometimes I Live in the Country, and W. G. Sebald’s The Emigrants, and Michael Tisserand’s biography of George Herriman, which might need its own post.

American Salvage, Bonnie Jo Campbell

This collection was a finalist for the National Book Award in 2009, having received much acclaim for its depiction of an under-represented Middle America—small-town folks of limited means struggling to make do. Knowing this, it’s somewhat of a challenge not to regard the characters as though they are creatures in a cage. If the book had been published now, they would certainly be compared to Trump voters—there is the right combination of frustration with themselves and suspicion of anyone who might be in a position to offer a solution.

The title, of course, alludes to more than the salvaging of machine parts or the useful portions of a slaughtered animal, though those things do occur here. The stories seek to pit characters against the strictures of economy and geography and addiction. But too many moments have been stripped of what ought to have been a more informative nuance. When Campbell writes of a character named Jim Lobretto, “He might have left the can outside the door while he paid, but knowing his luck, some bastard would steal it,” it’s not clear whose voice we are reading; the free indirect style is not apparent elsewhere in the story. There are a number of similar instances where the language leans on arbitrary swearing to remind us that these are frustrated characters long past the point of caring what someone from out of town might think. It’s as though we should expect them to want to be elsewhere, with a wide-angle awareness of their options, which I suspect is not how people in such situations actually live.

Where I’ve Been, and Where I’m Going, Joyce Carol Oates

I have never read a Joyce Carol Oates novel. I read some stories in school, though I can’t remember what they were, and I have read her essays and reviews. I read her warm and effusive encomium to Hill Street Blues that was published in TV Guide in 1985; it formed the basis of an essay I wrote on the magazine’s onetime role as a critical evaluator of television. I saw Foxfire once on cable. Jenny Lewis is in that one; she’s a singer now.

I had hoped that the Hill Street Blues essay would be included in this collection. What is here is a miscellany of book reviews, scholarly essays, and introductions to both Ms. Oates’s and other writers’ works. She is, of course, a wise reader with a great depth of knowledge of traditions ranging from myths to poetics and painting to her pet interests, boxing and serial killers. I was glad to see essays here on Fitzgerald and Grace Paley, whom I’ve recently read, and of course John Updike, who arose to fame concurrently with Oates and who has been viewed as a rival in both profligacy and relevance.

The first section, “Where Is an Author?” takes on broader challenges about art and the challenges faced by the artist as she takes on fear, sin, and victimization. “Art and ‘Victim Art’” is a response to a 1995 essay by Arlene Croce in The New Yorker objecting to the dance show Still/Here by Bill T. Jones, in which images of cancer and AIDS patients are shown. Croce struggled with the task of reviewing a show “from which one feels excluded by reason of its express intentions, which are unintelligible as theatre”; as a work of art, it rendered itself “undiscussable”:

The thing that “Still/Here” makes immediately apparent, whether you see it or not, is that victimhood is a kind of mass delusion that has taken hold of previously responsible sectors of our culture. The preferred medium of victimhood—something that Jones acknowledges—is videotape (see TV at almost any hour of the day), but the cultivation of victimhood by institutions devoted to the care of art is a menace to all art forms, particularly performing-art forms.

I have heard the same disparagement spat forth for what is called “Therapy Art”—the effort to utilize art to reassume control, to touch upon and rewrite pain, as though apology for daring to put forth one’s contribution were sewn into the lining. It is not a coincidence that a lot of such art is created by women; Frida Kahlo’s paintings and Plath’s The Bell Jar might unfairly attract this label.

The revulsion of victimhood and the seeming embrace of victim identity seems to inflame a lot of the criticisms of our contemporary activist organizations, such as Black Lives Matter and the Women’s March on Washington, in our present dialogue. Writing in 1995, long before such organizations flourished, Oates sees a problem:

The very concept of “victim art” is problematic. Only a sensibility unwilling to grant full humanity to persons who have suffered injury, illness, or injustice could have invented so crude and reductive a label.

There’s an acceptance that aggressors—in war, in capitalism, in sex relations—are entitled to all of the complexities that humanity entails; victims are simplistically reduced to what they have been stripped of or denied. But with art and criticism that imbalance steers a warped conversation:

Through the centuries, through every innovation and upheaval in art, from the poetry of the early English Romantics to the “Beat” poetry of the American 1950’s, from the explosion of late-19th-century European Modernist art to the Abstract Expressionism of mid-20th-century America, professional criticism has exerted a primarily conservative force, the gloomy wisdom of inertia, interpreting the new and startling in terms of the old and familiar; denouncing as “not art” what upsets cultural, moral and political expectations. Why were there no critics capable of comprehending the superb poetry of John Keats, most of it written, incredibly, in his 24th year? There were not; the reviews Keats received were savage, and he was dead of tuberculosis at the age of 25.

Another Brooklyn, Jacqueline Woodson

I have more Brooklyn novels than I can read, and I have read plenty, from Alfred Kazin to Hubert Selby, Jr. (but not Jonathan Lethem), but this one uses a poet’s language to bring the streets alive. It makes its center the heartache of adolescence, barely disguised from the author’s childhood. As crushes slip from August’s grasp and friends become pregnant, the tone of the neighborhood shifts:

From that window, from July until the end of summer, we saw Brooklyn turn a heartrending pink at the beginning of each day and sink into a stunning gray-blue at dusk. In the late morning, we saw the moving vans pull up. White people we didn’t know filled the trucks with their belongings, and in the evenings, we watched them take long looks at the buildings they were leaving, then climb into station wagons and drive away.

The Argonauts, Maggie Nelson

A well-liked book that is about bending genre as much as gender. As Nelson writes about building a relationship and family with her fluidly gendered partner, she reads herself with a poet’s critical eye, citing thinkers ranging from Gilles Deleuze to Lucille Clifton to Wittgenstein. It’s an intense mashup, interspersing the theoretical with domestic, intimate scenes, and turns what would normally be abstruse queer theory into very real art. It is most remarkable when even its quotidian moments invite a socio-critical lens. Commenting, for example, on an old family photo emblazoned on a ceramic mug:

But what about it is the essence of heteronormativity? That my mother made a mug on a boojie service like Snapfish? That we’re clearly participating, in a long tradition of families being photographed at holiday time in their holiday best? That my mother made me the mug, in part to indicate that she recognizes and accepts my tribe as family?

Scrapper, Matt Bell

Set in “The Zone,” the abandoned center of Detroit, Scrapper conveys with gloom and angst the haunted vastness of cities. A young man named Kelly rummages through old homes, factories and warehouses to strip them of their copper, gold, and whatever other scrap metal he can find and resell on the black market. So much of the book lives in its dark internality, not just because Kelly works alone but because he’s instinctively a nonverbal creature. This allows Bell to stuff the book with long, creeping paragraphs of thought and memory, though the chunks don’t always reveal much, instead seeming to set the mood with their murmur:

Kelly thought the world wasn’t full of special objects, only plain ones. Nothing was an assembled special, nothing and no one, but the plainest objects could be supercharged by attention, make nuclear by suggestion. He could pick up the same object in two different houses and in one sense a completely different thrumming. What he wanted was anything loved.

Kelly is a former wrestler, and in his echoing head, and his attraction to fitness as an escape and for control, he has a spiritual twin in the ex-soldier Skinner in Atticus Lish’s celebrated novel Preparation for the Next Life. His attentions turn to the pursuit of justice after he discovers a 12-year-old boy chained naked to the bed in one of the houses. The tension that unfolds in the remainder of the book relies on the reader’s investment in the revenge that Kelly seeks toward the boy’s abuser. In a city that is full of holes and bereft of order, though, revenge does not feel like an honest motivator.

Hunger: A Memoir of My Body, Roxane Gay

I bought Hunger while vacationing in Portland, Maine, and finished it before the vacation was over, it’s that good a read. It is also a memoir that holds up its responsibility of having something to say. The primary topic of the book, Gay’s struggles with obesity since childhood, allow for more open digression on the portrayal of bodies and eating in mass media and the facile approaches that our medical industry takes to nutrition. It is searing and honest, particularly with its slow looks at triggering events, in particular the author being the victim of a gang rape by neighborhood boys at the age of twelve. In reaction, the preteen Gay finds comfort in food:

What I did know was food, so I ate because I understood that I could take up more space. I could become more solid, stronger, safer. I understood, from the way I saw people stare at fat people, from the way I stared at fat people, that too much weight undesirable. If I was undesirable, I could keep more hurt away.

The chapters in Hunger are short, and the sentences patient and for the most part contractionless, so the tone is one of reflection. The social aspects of having a large body invite a number of angles, and Gay takes on all of them. “There are so many rules for the body,” she writes in a chapter on The Biggest Loser, “often unspoken and ever-shifting.” She writes about the “unspoken humiliations” that come with a judgmental gaze at an oversized woman. “They can plainly see that a given chair might be too small, but they say nothing as they watch me try to squeeze myself into a seat that has no interest in accommodating me.” There are sighs from passengers when she boards an airplane. And there is society’s temptation to correlate a lack of control in one’s body to lack of discipline in one’s character.

The Autograph of Steve Industry, Ben Hersey

This novel from Magic Helicopter Press, by a local author, came recommended to me by a friend at AWP. Set in Massachusetts, it covers every local landmark I ever knew in my childhood, from Kelly’s Roast Beef to Richdale to Route 1 South to yes, even candlepin bowling.

Playing that bingo game is only part of the fun of reading The Autograph of Steve Industry. Its narrator is the frontman of a rock band called The Steamrollers, and his marriage to Saundra, the mother of his young daughter, is on the rocks. Providing the framework of the book is a set of odd and feckless survey questions that the narrator uses as a jumping-off point, in many cases hardly provided “answers” in the traditional sense at all. Steve’s inclinations are torn between angst, rage, and pathos—a desire to do his friends and loved ones good without sacrificing what little he knows to be true about himself. A novel about an adult man who makes a fetish object out of his own aimlessness might sound frustrating, but the energy of the novel resides in the electric voice that Hersey gives Steve, one that riffs and buzzes like a guitar.

The Autograph of Steve Industry is excerpted here and here.

How to Get Into the Twin Palms, Karolina Waclawiak

This book is set in Los Angeles, but it’s a different kind of Los Angeles from the one laid out by golden dreamers or even Spanish-speaking immigrants, it’s the Los Angeles that’s nestled amid the freeways and motels and low-slung apartment buildings. The narrator is a Polish woman, Anya, who calls bingo games at the bingo hall and seems to exist among a community of strangers without really interacting with them. She lives across the street from the exclusive title nightclub and becomes obsessed with its Russian owners and clientele, literally watching parking lot trysts from her balcony. Los Angeles is a show to her and she seems, for some reason, to want a part. She finds a way in through Lev, a somewhat gruff Russian gangster-type who provides both sex and challenge for Anya. There are multiple levels of alienation and exclusion at play here, and the disjointed narrative—which at times pinballs between languages–creates a mood of ill communication and driftlessness:

I stood up and stared at him. Gathered the half-smoked, crushed cigarettes in my hand and started walking away from him.

“You were walking in front of your window. Nearly naked. What could I do?”

I don’t know why but looking at him—his face swollen and ruddy—I wanted him to work harder.

He should have begged.

I didn’t answer him but just kept walking. Toward the alley and toward the dumpster. He followed me, close. I could hear his steps, his attempt to get in line with mine. He was following me to the dumpster. I crossed pavement and dumped the cigarette butts in the bin, turned on my heel and stared at him.

“All that for a few cigarettes?”

I had embarrassed myself by being overly dramatic.

“You American girls are all the same.” He started walking away.

“Like what?”

“Zanudi.”

I searched for a Polish translation. Something similar.

Zanduzać.

Nudzić.

It all meant the same.

Boring.

This Is Not a Confession, David Olimpio.

I’ve met Olimpio twice, and got this book signed by him at AWP last spring. These linked essays are mostly about his childhood and family, and they are explicit about incidents, most notably the sexual abuse that the author suffered at a young age by a babysitter. And while the title invites the kind of self-questioning that Magritte similarly prompts, making you wonder if you are reading a riddle, there’s also a suggestion that we as a reader are not being invited to make judgments. This is just what is. This is what happened.

Olimpio sifts and strains the language in these pieces so that the irony of the title does not tinge what is inside. The first set of essays are about time and relativity, which tacitly brings to the surface questions of memory and distance and immediacy. He does not shy away from details about his babysitter’s abuse, nor the extramarital relationships he undertakes as an adult, and the juxtaposition of their telling invites an interpretation of behavioral cause and effect. Some of the stories are, frankly, what might be called TMI, and in some the journey doesn’t generate enough of a lesson to pay off. He remembers whole conversations in a way I have found suspect in the work of other memoirists, as though he knew when he was having the conversation that he would later be writing about it, but this could also speak to the effect of what the writers trains himself to observer and remember, especially when working from experience. If this is indeed not a confession, with whatever odor of guilt that word connotes, there’s some other fair motive for justifying their sharing, even if it’s the author’s chance to clear his head.

An excerpt from This Is Not a Confession can be found here.

Potatoes in Minutes at Bodega

July 4, 2017 § Leave a comment

And as I have a walk around, other things sound like they’re ready to fall apart, like the refrigerator rattling only because (perhaps? hope to God?) a pickle jar is jammed against the compressor. I hear scratches and try not to think about what has nested in the walls.

I have a new story, “Potatoes in Minutes,” up at Bodega as part of Issue #59, alongside poetry by Cassie Duggan, Dacota Pratt-Pariseau, and Barbara Tramonte.

Anyone who knows me will see a lot of real life in this story. “Potatoes” was one of two stories I workshopped at last year’s Catapult Online Fiction Workshop taught by Justin Taylor, and I’m pleased that it’s found a good home.

Thanks to Melissa Swantkowski and the editors at Bodega for picking this up.

The Highbrow Era of TV Guide at Electric Literature

June 15, 2017 § Leave a comment

But in its best years, TV Guide was more than a guide; it allowed you to participate in the cultural conversation of television even through those shows you never watched, like you might read The New York Times Book Review about books you don’t ever plan to read. Before the Internet was available to host this conversation, TV Guide was the document that brought it to the masses, physically and metaphorically denser than the gossipy, photo-filled space-holder we find in the supermarket today. Its editors were determined to ensure that Americans embrace television as serious, even highbrow art.

Up at Electric Literature today I am thrilled to have a new essay about a magazine that was can’t-miss weekly reading in my formative years: TV Guide.

This piece is new critical territory for me and I’m grateful to editor Kelly Luce for giving it an excellent home.

Head under Water at Prick of the Spindle

May 30, 2017 § Leave a comment

If they liked you, they’d remember you. And every once in a while a kid pops back in to say hello. A little fuller in the face, a little more run-down. Out of the Army or Marines with erect posture, rounder head, clearer gaze. The women thicker in the hips, more sass, more sashay.

They shake hands with their old principal and say hey there, Mr. Rush, you’re lookin’ good, and they chat Edwin up, because they want to retrace things and show him they’re different people now, they talk a different game.

At Prick of the Spindle today I have a new story, “Head under Water.” It’s by far the longest story I’ve ever written, and “new” is a bit of a relative term, as it turns out that according to my records I’ve been working on the story in some form for over eleven years. It’s undergone several substantial revisions and at least three title changes. I’m glad for it to have found a home in what is definitely its final form, and I’m grateful to editor Cynthia Reeser for picking it up.

Drawing Names

May 13, 2017 § Leave a comment

Last November, when we visited Montreal, we made a trip to Librairie Drawn & Quarterly, an edgy bookshop known for its sweet selection of graphic novels. This is from Mile End, by Michel Hellman, which I have been reading slowly with Bing Translate close at hand. Though I took five years of French in school and two more semesters in college, I don’t hear it well enough to maintain a conversation. Reading the words essentially as captions to illustrations has provided a fun and useful way to brush up on my French and learn about life in the Mile End neighborhood of Montreal (where Librairie Drawn & Quarterly happens to be).

Perhaps with cartoons on the brain, yesterday I went for a walk into town and came back with Michael Tisserand’s Krazy: George Herriman, a Life in Black and White, an exquisitely designed brick about the curious life of the man who created Krazy Kat and Ignatz Mouse.

Herriman was born in New Orleans, of Creole descent to a family that took pains to hide its African-American heritage. That peculiar backstory seems to inform a lot of the mischief and anarchy that came through in the Krazy Kat comics. This is going to take me a while to get through.

Zoo Stories

April 16, 2017 § Leave a comment

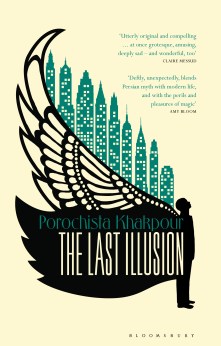

Last Friday night, in Amherst, I attended a reading by Porochista Khakpour, author of the novels Sons and Other Flammable Objects and The Last Illusion.

Born in Tehran, Khakpour immigrated with her family to the United States as a young child. It was interesting to hear her stories of growing up in a bilingual household and discovering her love for literature by way of the western-canonical writers she thought she was supposed to like (Shakespeare) before discovering the ones that spoke to her (Faulkner).

She told about growing up in a country that, in the eighties, went out of its way to telegraph its hatred for her people, a country where FUCK IRAN buttons were sold in grocery stories.

Khakpour read an essay originally published in Guernica titled “Camel Ride, Los Angeles, 1986,” about a childhood trip to the Los Angeles Zoo and her father’s stubborn insistence that his children enjoy a ride on a camel, notably his refusal to see the implications of a Middle Eastern family riding a camel for the amusement of westerners.

Out loud he said, “Are you ready? Come on, everyone! This is what you’ve been waiting for!”

What we’d been waiting for was more likely a place where we could be like everyone else, rid of a certain yellow and maroon script, rid of rides on the backs of things or just the idea of us riding on the backs of things, especially that thing. We were somewhere else altogether.

The Last Illusion adapts a tale from the Persian Shahnameh and projects it onto a backdrop of post-Y2K and pre-9/11 New York City. The main character, Zal, is a “bird boy” who was raised in a cage by his mother. He is rescued by a psychologist named Hendricks, who specializes in the study of feral children. In the original poem from the Shanameh, Zal is an albino child, whose paleness causes his parents to abandon him on a mountain.

At the same time, an illusionist named Silber seeks to perform one final stunt—to make the World Trade Center disappear. Intrigued by Zal’s freakish tendencies, he ropes the boy in as an assistant. Zal has odd birdish habits—such as eating insects covered in yogurt—and a desire to fly, a talent that Silber had demonstrated in his earlier spectacles. Zal’s girlfriend, Asiya, has odd eating habits as well–she’s an anorexic–and she experiences premonitions of disaster that cast a surreal pall. The reader, of course, knows exactly the disaster of which she speaks. So we get a novel that interweaves themes of flight and escape, showmanship, and the establishment and rebirth of identity against forces both resistant and inevitable. For that reason it reminded me of Michael Chabon’s Pulitzer Prize-winning The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay.

Khakpour has a memoir coming out next year, titled Sick, about her battle with late-stage Lyme disease.

My Father, the High Line at Catapult

April 7, 2017 § Leave a comment

I have a new essay up at Catapult this week, the first long personal essay I’ve ever published. It’s called “My Father, the High Line“:

Given the opportunity to boast of a prize catch and back it up with evidence, along with some cat-and-mouse hijinks to boot, my father remained forever silent, leaving us to discover the story only after he was gone, folded along with his tube socks.

I’m grateful to editor Mensah Demary for picking this up, and for his editorial guidance.